Why I Don’t Love OKRs

The question is not which framework to choose. The question is, how do we succeed as a company? On Objectives, OKRs, NCTs — lessons from reinventing the company goal setting.

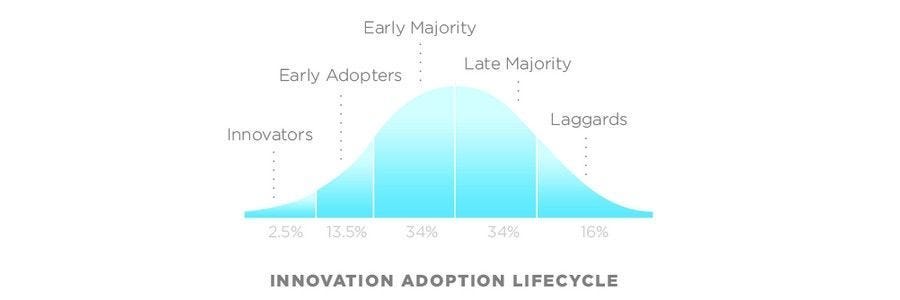

Let me tell you something about myself: I have a limited tolerance for bullshit. When someone approaches me with a new company goal-setting framework, I’m not an early adopter. I’m a laggard or, at best, part of the skeptical late majority.

“But what for?” — that’s my usual response. Another fad? No, thank you.

Fads and fairy tales

Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) seemed reasonable - definitely better than having no objectives at all. But I wondered: are OKRs just another fad, or are they a long-lived trend adopted by many yet understood by few?

Sometimes, I get consulted about all things Agile from people working in very traditional command-and-control environments wanting to implement OKRs. "The management will feel so good about themselves if we did OKRs!" is what they're thinking. " " is what they're really doing.

How does one explain that for anything to work, you need a solid foundation and not just a catchy trend?

What are the OKRs?

Let’s get back to the Objectives and Key Results. What are they?

My favorite conspiracy theory is that OKRs were invented as a psyop from Google to slow down other companies:

As explained by John Doerr, the greatest evangelist of OKRs, the abbreviation stands for Objectives and Key Results:

An Objective is simply what is to be achieved. By definition, Objectives are significant, concrete, action-oriented, and (ideally) inspirational. When properly designed and deployed, they’re a vaccine against fuzzy thinking and ineffective execution.

John Doerr, Measure What Matters

Key Results exist to drive progress toward the Objective. The key question to ask is, "How will we accomplish it?" They also serve as a clear measure of whether the goal has been achieved.:

Key Results benchmark and monitor how we get to the Objective. Effective KRs are specific and time-bound and aggressive yet realistic. Most of all, they are measurable and verifiable. You either meet a key result’s requirements or you don’t.

John Doerr, Measure What Matters

On paper, it looks fantastic. If I worked at a company already using OKRs, I'd focus on making them truly effective. I’d be crafting inspiring goals, getting everyone pumped with the Bono speech — after all, inspiration fuels engagement! And backing everything up with solid data to create meaningful Key Results. You get the idea.

As Agile As a Steam Train

Maybe it is not the OKRs I am not a big fan of, it’s more how companies adopt them. Typically, a company brings in an OKR guru to roll them out—someone external with zero understanding of the company’s culture, business, or reality. And off they go.

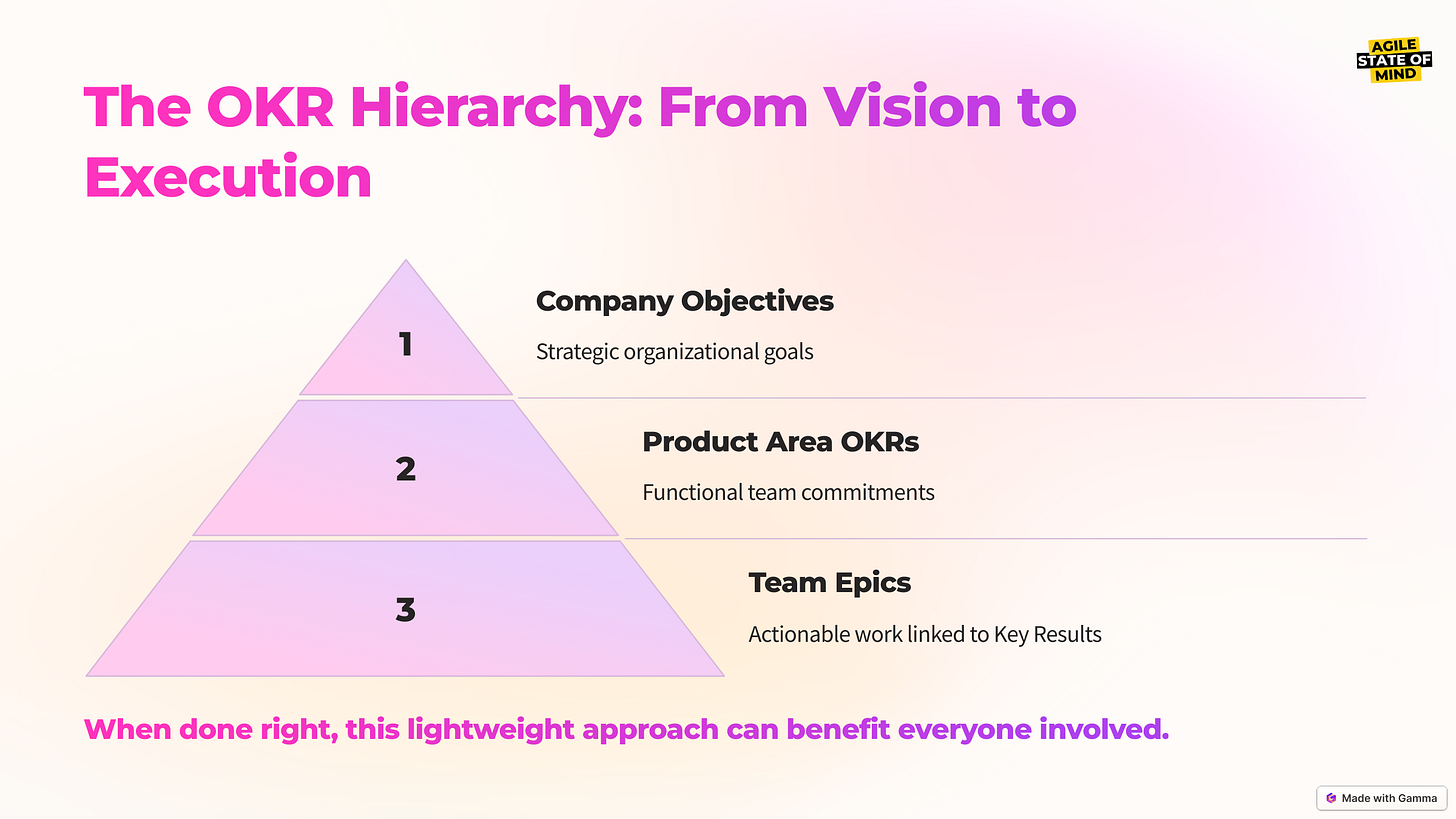

What follows is a never-ending marathon of the creation and iteration starting with the OKRs for the exec team. Then, higher and middle management craft their OKRs based on those. Afterward, each and every team has to do the same. Yes, it’s a full-blown OKR waterfall.

The spreadsheet containing this OKR cascade starts crawling like an old steam train, barely moving unless you keep shoveling coal into it. Eventually, you reach a point where you need to upgrade everyone’s laptops—just so they can open the damn spreadsheet. lol.

(If you’re wondering: Yes, been there. Done that.)

That said, the framework is only effective if its implementation is kept simple. No monster spreadsheets.

A better approach? Annual company-wide goals combined with quarterly OKRs at the team or product line level. I prefer OKRs at the product level since team-based ones often lead to siloed goals that impede collaboration.

A Practical Problem

It’s not just the endless OKR setup and the hassle of everyone having their own. The real struggle is crafting inspirational goals with meaningful Key Results.

Take a simple example—let’s say we need to deprecate a tool. The first instinct? Write a goal like:

O: Deprecate the steam train.

And the KRs will be something along the lines of:

KR1: Complete the necessary railway traction enhancement.

KR2: Train the conductors to run an electric train.

KR3: Complete the electrification of the tracks.

(Side note: This is a real example, just adjusted for the railway world. And yes, it’s an antipattern.)

Are you excited to work on your goal yet? Didn't think so.

You might be wondering—what does “complete” even mean? Do we need 100% of the tracks electrified? By when? Do we have a century to get it done?

The answers probably exist somewhere—maybe buried in an epic, hidden in a PRD, if you are lucky to have one, or locked inside a Product Manager’s head. However, if you are new and look at the OKRs you will have no clue what they mean, not to mention why we should even do this. And by keeping Key Results vague instead of giving teams real direction, we’re just increasing confusion

The Power of Context: Why OKRs Need a Story

Imagine it’s the late 1800s. Steam trains are chugging across the United States, fueling industrial expansion, connecting cities, and moving goods at an unprecedented scale. Then, someone proposes a bold idea: electrification. Overhead wires, new infrastructure, and a radical shift in how trains operate.

Naturally, people start asking questions. Why should we spend huge amounts of money on electrification if steam trains are already up and running? What’s the actual value? Won’t overhead wires cause more problems than they solve? Have we even considered alternatives, like diesel-powered trains?

These are valid concerns. And in the absence of a compelling narrative—one that clearly articulates the long-term benefits of efficiency, lower operating costs, and environmental sustainability—the idea doesn’t gain traction. Instead of embracing electrification, the U.S. largely stuck with steam and later transitioned to diesel. Meanwhile, countries like China invest heavily in rail electrification, resulting in over 64,775 km of high-speed rail today, compared to the U.S.’s mere 6,071 km (as reported by World Population Review. ). The lack of a strong, widely understood context led to what many now see as a lost opportunity.

Now, let’s bring this back to OKRs.

Even if the reasoning is explained during an OKR presentation, that context is often forgotten, misunderstood, or simply overlooked. And let’s be honest—how many people are going to dig through old all-hands slides to refresh their memory? That’s assuming the rationale was ever clearly explained in the first place.

A well-defined objective needs more than just a goal and key results—it needs a story. A compelling ‘why’ that makes people care, understand, and align their efforts accordingly.

Without it, even the most well-intentioned objectives can become missed opportunities—just like railroad electrification in the U.S.

Meaningful OKRs

For OKRs to truly work, we need to set quality goals—ones that go beyond just “completing a task.” Sticking with our steam train example, a more meaningful goal would be:

O: Expand the coverage of faster, more efficient and sustainable electric trains by replacing the remaining steam trains

The Key Results might look like this:

KR1: Increase railway traction enhancements on Tier 1 (busiest tracks) from 40% to 80% by the end of Q2.

KR2: Ensure 100% of conductors on Tier 1 and Tier 2 receive electric train training by the end of Q1.

KR3: Increase Tier 2 track electrification from 60% to 90% by the end of Q1

However, when working with a new and complex product—one that most people don’t fully understand and whose vision is still scattered across the minds of a few (often misaligned) leaders—things can easily go off the rails.

This is the reality for many companies, especially startups. In these cases, OKRs alone won’t cut it. People need context. They need to understand the why, the bigger picture, and the customer problem that actually needs solving.

When is Enough Context Enough?

I advocate for sharing context with everyone. Providing just a goal without explanation can lead to misunderstandings and hinder deeper engagement.

There are numerous stories of individuals driven by personal bonuses who, in their pursuit of personal goals, inadvertently jeopardized their companies. We don’t want just a shallow activity of moving the metrics, we want an understanding of value creation for the company.

I don't have all the answers regarding how much context to provide teams. I invite all of you to share your ideas and practices for ensuring a better understanding of company strategy and the intent behind goals.

A Narrative for Success

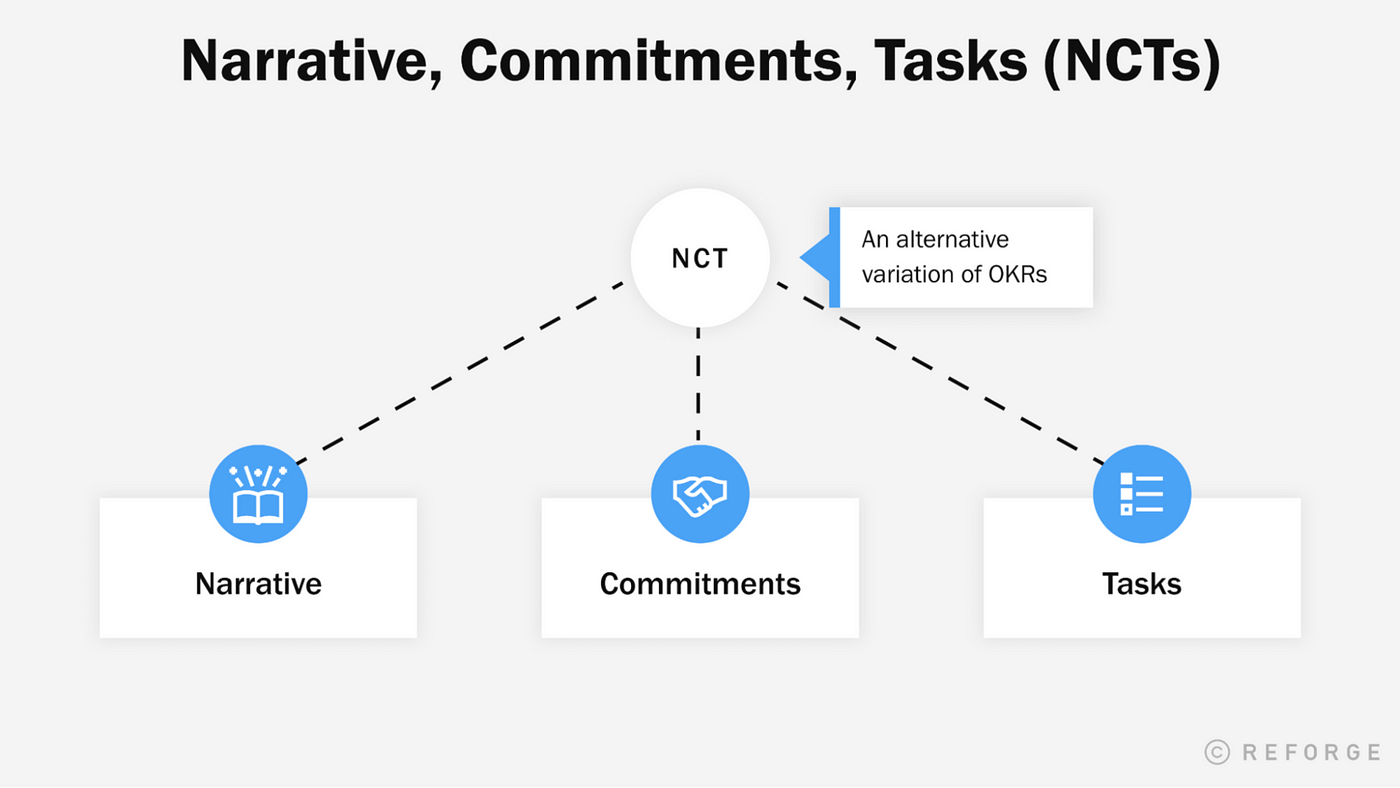

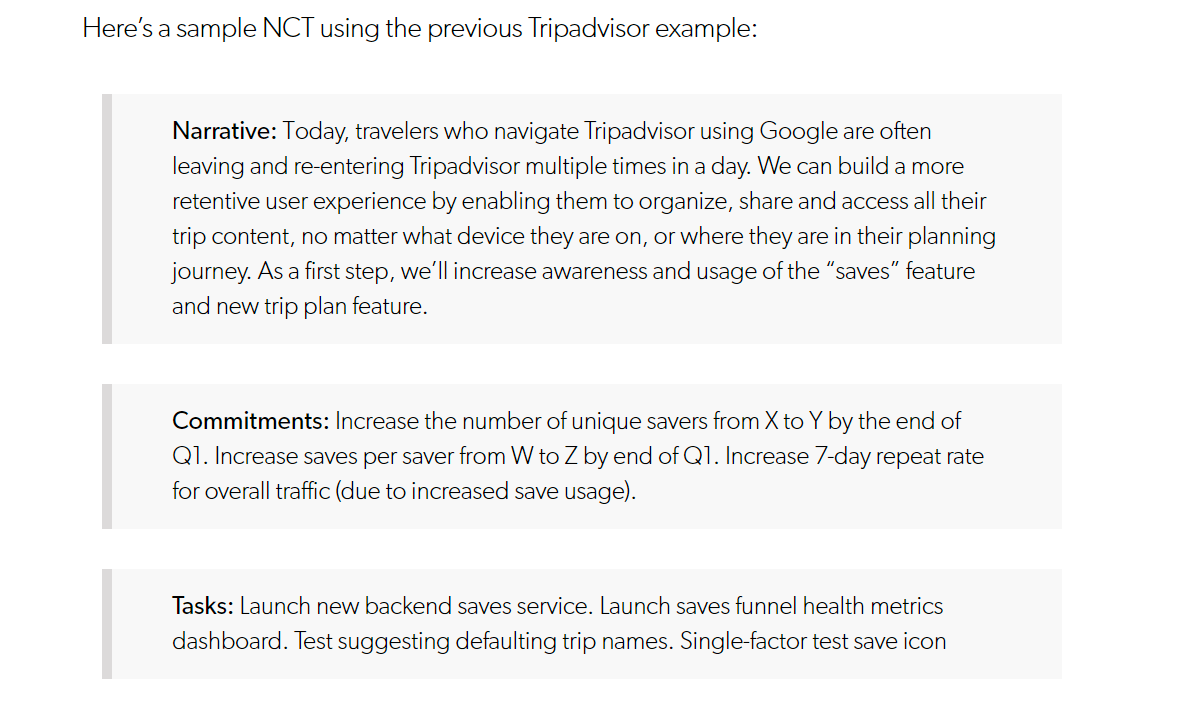

In my search for answers, I came across a simple framework that helps employees understand the why behind goals: NCTs — Narrative, Commitment, Tasks.

Yeah, another three-letter acronym. But this one got me because it addresses the missing narrative in OKRs—or maybe just because I found it myself…

I also relate to the problems Reforge article highlights, like:

“Teams set lofty goals, often to impress leadership, without also establishing actionable commitments that will enable the team to actually achieve the goal. When inevitable failure comes, teams lose credibility and maybe even start doubting their own skills.”

Reforge

This is a side-effect of leadership’s failure to provide a strategy:

“There’s nothing wrong with trying to improve retention by 5%. But teams also need to align around a pragmatic plan for how to get there, rather than throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks.”

“For example, before goal-setting around improving retention, teams should know what retention is composed of, which levers are likely to move it, and which solutions effectively pull those levers.”

Reforge

A Different Goal-Setting System

Here is what the framework looks like:

I won’t dive into the details—you can check out the Reforge article for that. But I will share an example of TripAdvisor’s goal-setting approach that I found on Twitter and found particularly compelling:

OKRs Without Narrative

OKRs can be a useful tool, especially for mature companies with a clear, shared understanding of their product. If stakeholders provide enough context or if the product is inherently easy to grasp (think Spotify, Netflix, Uber, Free Now, Tinder, or Bumble—assuming you’re not too embarrassed to admit using them), then OKRs can work very well.

Avoiding the Certainty Illusion

Maybe what we’re really trying to do here is avoid over-commitment and the false certainty of a Gantt chart. Instead of fixating on features and rigid deadlines, we focus on objectives and delivering value within a realistic timeframe.

Ultimately, the goal is to redefine roadmaps—shifting towards understanding the problems, the why behind them, and collectively finding the best solutions. Something along the lines of what Claudia Delgado describes in “A Modern Roadmap”:

I’d love to hear your thoughts! How do you approach goal-setting and roadmaps? What practices have worked for you?

Have you tried setting OKRs in your company? Share, share, share!

Subscribe and get the OKR cheatsheet that summarizes this article with a BONUS: my OKR prompts to AI!